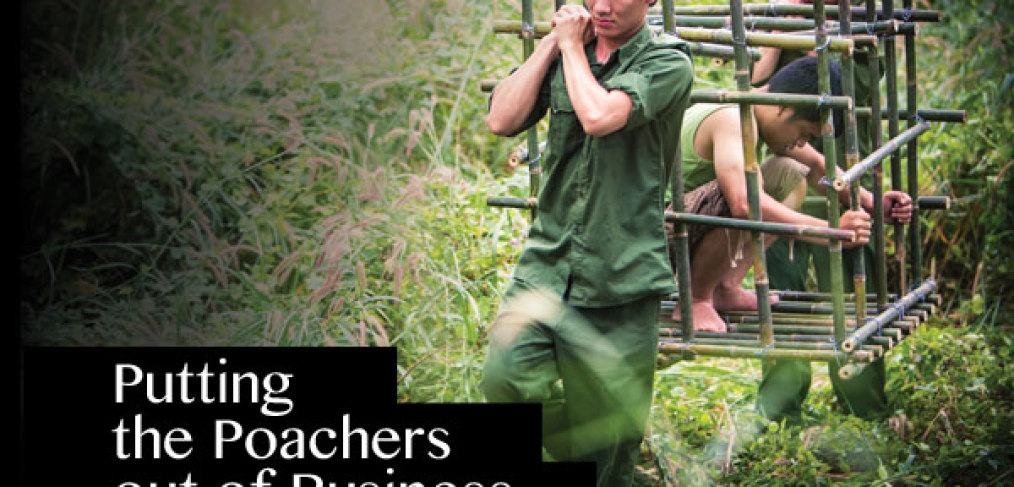

Putting the Poachers out of Business

The trade in animal parts is a multi-billion-dollar business that rivals drug and human trafficking in its global reach. In an exclusive article published simultaneously in Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam, AsiaLIFE goes in search of the criminals involved in the industry and those tasked with preventing and punishing them. Bridget Di Certo, Chris Mueller and Mark Bibby Jackson. Photo by Alex McMillan.

The trade in animal parts is a multi-billion-dollar business that rivals drug and human trafficking in its global reach. In an exclusive article published simultaneously in Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam, AsiaLIFE goes in search of the criminals involved in the industry and those tasked with preventing and punishing them. Bridget Di Certo, Chris Mueller and Mark Bibby Jackson. Photo by Alex McMillan.

The photograph shows a man sitting on top of a tiger. He is holding a rifle in his right hand. The tiger is dead.

Taken on a mobile phone in Thailand’s Western Forest Complex, the image was used to convict Thai national Nai Sae Tao to five years imprisonment in February this year — the most severe punishment handed out for wildlife poaching in the country. His partner in crime, Vietnamese Hoang Van Hien, received a four-year sentence.

The global trade of wildlife is big business. According to wildlife NGO Freeland, some experts estimate it at $10-20 billion annually, and it is growing.

“Over the past few years wildlife trafficking has become more organised, more lucrative, more widespread, and more dangerous than ever before,” US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, said at a meeting on wildlife trafficking held at the State Department in Washington last month.

The very fact that Clinton was addressing an international convention on trafficking emphasises the importance being placed on the issue by policy makers. Left unchecked the impact on nature could be devastating.

“If trends continue, scientists predict 13 to 42 percent of Southeast Asia’s animal and plant species could be wiped out this century,” according to Freeland. “At least half those losses would represent global extinctions.”

Trafficking Across Borders

It is not difficult to see the trappings of animal trafficking across the region.

The streets of Vietnam are teeming with wildlife. In urban centres, cages perched on the backs of motorbikes are stuffed with wild birds, lizards, marine animals and sometimes monkeys on chains. Many are endangered.

In some markets, in clear view, hawkers sell rhino horn and tiger bone paste, the authenticity not known. Wildlife restaurants are common, selling rare meat to those looking to impress their peers or trying to cure some real or imagined ailment.

In August, the last remaining male in a herd of elephants in Vietnam’s south-central Dak Lak province was killed for his tusks. Conservationists now say the herd is unsustainable. The New York Times later wrote about the incident, stating that elephant conservationists in Vietnam had “essentially thrown in the towel”.

“I think we’re getting very close to there being no hope for the elephants [in Vietnam],” says Nick Cox, the manager of WWF’s regional programme on species and protected areas

Vietnam is also playing a larger part in the thriving tiger parts trade, which they use in traditional medicines. Although the trade is officially illegal, licensed tiger breeding farms — formed by the Vietnamese government as pilot programmes for reintroducing tigers into the wild — still exist.

Conservationists warn they could be fronts for the trade. Cox says that tigers are virtually extinct in Vietnam and, as it’s not cost-effective for poachers to hunt wild breeds, more farms are popping up to meet growing demand both in Vietnam and in China.

Catching the Poachers

The problem is not unique. In October, a man was arrested in Khon Kaen province in northeastern Thailand while driving a truck containing 16 tiger cubs. Police said he was paid $470 by an unnamed trader to transport the animals from Bangkok.

According to Wildlife Friends Foundation Thailand (WFFT), the cubs came from breeding facilities in the Kanchanaburi and Greater-Bangkok regions. It believes they may have been destined for the Laos city of Thakhek where “one of the largest ‘safehouses’ for wildlife is, with dozens of bears, tigers and hundreds of pangolins awaiting transport to Vietnam and China”. The driver claimed he did not know that the transportation of tiger cubs was illegal.

Zoos that have legitimate licenses for breeding tigers could also be part of the illegal trade, reports indicate.

In April the owner of a private zoo in Thailand’s Chaiyaphum province was charged with possession of protected wildlife after two tigers cubs were found during a July 2011 raid. At the time, DNA samples were collected to verify claims that the cubs were the offspring of animals legally owned by the zoo.

A subsequent DNA test conducted by the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation’s Wildlife Forensic Science Unit showed the claims were false. The zoo is believed to be a cover for illegal international trafficking operations, according to Freeland.

“What traffickers must understand is that Thailand is very serious about wildlife crime and will continue to use the latest forensic techniques to investigate and apprehend these organised criminals,” says Doug Goessman, law enforcement advisor for the wildlife organisation. “CSI and forensics not only applies to people, it applies to wildlife as well.”

The use of DNA is just one of the many modern approaches law enforcement agencies are using to clamp down on the poachers.

In Thailand’s Western Forest Complex, rangers are trained in GPS control systems to monitor the movements of protected wildlife and their prey. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) says such technology has helped to improve rangers’ morale, which was “very low” when the group started working in the area in 2005.

“The key thing is to maintain the quality of the protection in the park,” says Anak Pattanavibool, director of WSC Thailand.

Training, improved job satisfaction and the use of modern technology all help to achieve this, and the results are showing. The Western Forest Complex is one of the few places in the world where the number of tigers is actually rising. “It’s quite amazing,” Pattanavibool says. “The wildlife population is responding quite positively.”

Technology also helped in the conviction of Nai Sae Tao and Hoang Van Hien. Evidence provided by camera traps proved the tiger they killed came from the Western Forest Complex, rather than across the border in Myanmar as the poachers had claimed. It seems tigers have distinctive stripes that are almost as conclusive as human fingerprints for identification.

A Few Good Men

Those looking for more positive signs need to look across the border in Cambodia, where the wild animal trade was once rampant.

Just five years ago, many local markets and restaurants were involved to some extent in purchasing or trading wild animals for medicine or meat, according to conservation group Wildlife Alliance. It was a profitable business with high demand. In the mid-2000s, a healthy pangolin — a scaly anteater found in parts of African and Asia — could be sold for about $80 per kilo. Now it is around $300. Pangolins are in high demand, especially in Vietnam and China where they are sold as meat and their scales are used in traditional medicines.

Since then, renewed conservation efforts in Cambodia’s jungles have resulted in a major slowdown of the highly damaging and illegal trade, but that is not to say it does not still exist. In fact, the stakes are higher than ever as hunters and traders resort to extreme measures to continue their plunder of Cambodia’s forests.

“The scale of the problem in Cambodia is decreasing tremendously,” says Khem Vong, project manager of Wildlife Alliance’s Wildlife Rapid Rescue Team (WRRT). “It used to be that wildlife was openly for sale on national roads — trading was very out in the open but now it is more difficult to find wildlife meat.”

The trade has been driven underground by the successful actions of Khem and the small team of investigators and military police. The wildlife taskforce, in operation since 2008, cracks down on trading cartels and rescues and rehabilitates poached wildlife.

But the team has had to adapt to increasingly sophisticated and covert measures used by animal traders. Whereas animals like macaques were once transported by public bus from place to place and exported across borders — most frequently to Vietnam, traders now employ more clandestine methods of transportation.

“In one recent raid, we stopped a luxury car with fake military plates that had a sealed medicine box in the trunk. Inside were six rattlesnakes, each in a medicine compartment being kept on ice to keep them quiet and generate oxygen,” Khem says.

Dwindling populations mean that pangolins can now fetch up to $1,000. In part, this is due to large land concessions that can result in the razing of flora or fauna, says Nick Marx, director of wildlife rescue and care at Wildlife Alliance. “The big, charismatic, valuable stuff like tigers are simply gone,” he says.

A Lesser Crime

One problem in the region is that even when the poachers are caught the likelihood of conviction is slim and the punishment meted out seldom fits the crime.

“It’s still a long process preparing the case [even if] the police are willing to prosecute,” says Seamas McCaffrey, communications officer for Freeland. “It can be years and at the end of it all, they maybe just get a slap on the wrist. There are a lot of loopholes and gaps in law where cases can fall apart.”

The organisation has a programme aimed at informing those within the law and order network that it is a multi-billion-[dollar] trade, often linked to money laundering and other forms of trafficking. “Criminals see it as a lower risk way to make money because the penalties are just not as strong as for drug trafficking or human trafficking,” he says.

Although William Schaedla, regional director of NGO TRAFFIC, says the link between animal traffickers and organised crime is overplayed — the former requires specific husbandry skills that normal criminals do not posses, he agrees that there is a tendency to see animal trafficking as a lesser crime.

“The case evaporates and there is no follow through in the court system or prosecution,” he says. “Prison sentences when they are actually carried through are often very low.”

Wildlife at Risk (WAR), a grassroots NGO based out of Ho Chi Minh City, has an alternative approach, focusing on local education. It targets students rather than taking on lawmakers and fighting poachers directly. Simon Faithfull, a technical advisor, says the programme is popular, and many young Vietnamese are starting to understand the importance of protecting wildlife.

“There is no point in butting heads with local authorities,” he says. “Do you play a softer ball game or butt heads and have your project shut down?”

Sometimes new legislature can work to help rather than hinder the poachers. In October, Vietnam’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development legalised the commercial trade of 160 species they deem to be non-threatened. However, wildlife experts say many of the species are actually endangered. Others fear that it opens the door for hunters to capture or kill any species they come across by claiming misidentification.

“A lot of the species cannot be readily identified by the forest management, hunters or rangers,” says Douglas Hendrie, the wildlife crime and investigations advisor for Education for Nature – Vietnam (ENV), an NGO that works with the Vietnamese authorities to try to improve wildlife protection. “No one will know who is selling what and this will result in increased trade.”

Laws like this continue to complicate wildlife protection in Vietnam, but at the same time Hendrie says that such legislation, though ill-founded, had good intentions. The aim was to create a hunting law, like many in the west that are used to control the population of certain animals.

“A similar law is implemented in the United States, and there is nothing wrong with it,” Hendrie says. “But what’s wrong with this law here is that it is made for a Vietnam of the future, not the Vietnam of today.”

A Hub for Trafficking

The Mekong countries are not just feeder countries. They can also act as conduits for illegal animal products such as rhino horn and ivory from Africa, which are then exported to markets in China, the United States and Europe, often over the internet.

“Thailand is definitely a hub, you can tell that from the seizures that are coming in,” McCaffrey says.

Vietnam is another major culprit, according to the Wildlife Crime Scorecard, a report released in July by WWF. Since the last Javan rhino in Vietnam was officially declared extinct in October 2011, the Vietnamese have had to look to the white rhinos of South Africa to meet demand.

Many believe rhino horn has multiple medicinal properties that can cure anything from cancer to hangovers. Some consumers simply do not know that these animals are on the brink of extinction. Others blindly believe the claims made by the peddlers of illegal animal products, despite the lack of scientific evidence. Still more believe that offering endangered species to their dinner guests is an overt demonstration of their wealth.

Out of Business

Back in Thailand, the efforts of Anak Pattanavibool and the rangers of WCS show the way forward.

A combination of improved training, modern technology and transparent punishment of offenders has helped turn the Western Forest Complex into one of the most important sanctuary reserves in the region. The number of tigers in its Hua Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary has risen from 46 in 2007 to 65 this year.

The photograph of Nai Sae Tao striding the dead tiger appears on a Facebook page called Save the Tiger. More than 1,600 people have “liked” a story documenting the poacher’s capture, with some comments indicating the intensity of people’s feelings on the subject.

Their comments echo the sentiments of Clinton at the close of her speech. “Let’s put the poachers out of business and build a more secure and prosperous world for all of us, and particularly for children generations to come.”